- posted: Jul. 26, 2019

- Archive, Articles, Business Counseling, Employment, High Technology Law, Business, Uncategorized, Copyright, Small Claims, Political, Business Law, Crowdfunding, JOBS Act, Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, Business of Media, Trade Secrets, Consumer Credit, Trademarks, Securities Act, Securities Exchange Act, Incorporation/LLC, rights of publicity, Employment Law, Business Litigation, Intellectual Property

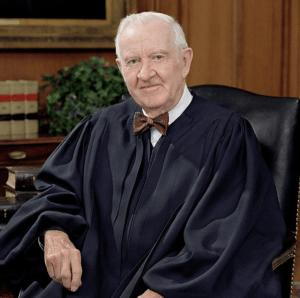

The Forrest Gump of the Supreme Court, former Justice John Paul Stevens, died on July 16, 2019, at the age of 99. Entitling him as “Forrest Gump” is to honor him, as being around some of the most significant events of the 20th Century. He met Amelia Earhart. He received from Charles Lindbergh a caged dove that Lindbergh had been awarded. He may have been the last person alive who was at Wrigley Field when Babe Ruth “called his shot” in 1932. The Justice’s verdict: Babe Ruth did indeed point at where his home run shot would go. He joined the US Navy the day before Pearl Harbor as a codebreaker, and was part of the group that figured out where Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was going, leading to the death of the man who “claimed he was going to ride down Pennsylvania Avenue on a white horse and dictate the surrender of the United States in the White House.” Lt. Stevens received a Bronze Star for his actions.

In 1975, President Gerald R. Ford appointed Justice Stevens to replace a legendary Supreme Court Justice, William O. Douglas. The US Senate endorsed his nomination, 98-0. But long before he became a judge, he was sensitized to what injustices our justice system can create: his father was wrongfully convicted of embezzlement, and an appellate court later reversed his conviction, finding no evidence of the crime. Justice Stevens was best known for his practical, fair application of the law, whether it was deferring to governmental agencies’ interpretation of their own statutes (Chevron USA v. NRDC: if the statute clearly shows the intent of Congress, court’s will enforce that intent, but if not, the agency’s interpretation is to be respected, unless “arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to the statute”) or Justice Stevens’ Supreme Court opinion in Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 US 417 (1984), also known as the Betamax case, was especially important in intellectual property. Certain entertainment studios sought to shut down the copying of broadcast shows as copyright infringement. Did copying a broadcast for personal use later constitute copyright infringement? This was not an ideological question. Both right-leaning and left-leaning judges joined both the majority and minority opinions. However, Justice Stevens’ theory of “time-shifting” – if you can enjoy a copyrighted work at one time (e.g., 8 pm on Thursday on a major TV network), you should be able to make a copy of the broadcast so that you can watch it at another time – is the legal basis for much of our modern entertainment regime. Judge Stevens was careful to balance the interests of both the entertainment producers as well as the consumers. The producers lose nothing if someone can watch a show at a time other than the broadcast time, as long as the recording cannot be reproduced again and again. Never mind the long-forgotten Betamax, digital recording today of 4K shows could not happen without this decision. Justice Stevens understood that not everyone could be in the right place at the right time.

Image: Justice John Paul Stevens. Photo by US Gov't.

By: Andrew K Jacobson