When you feel an invisible elephant stepping on your chest, you are probably having a heart attack. Unless you’re me. The 51-year-old Andy wasn’t having a heart attack, even though my mother had a terrible heart attack at 53. It was indigestion. It was a pulled muscle. I took some aspirin for the “pulled muscle” (though I was hedging my bets by then). Finally, I asked my wife Tamayo to drive me to the ER – and my odyssey through the medical system began.

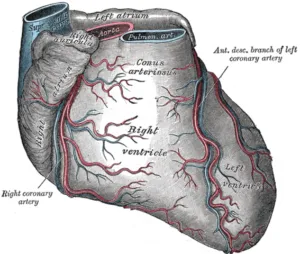

The Attack. First, an EKG – for about 5 seconds, when the assistant ripped the leads off and rushed me to the cardiology area, where he received  congratulations for getting me there so quickly. There I met the first of many new friends: Dr. Mitul Kadakia, my new cardiologist. He calmly explained to me that I was having a heart attack. I don’t remember much until the next morning, when I woke up in a hospital room. Dr. Kadakia told me that I had a massive heart attack – something had blocked the “Widowmaker,” my left anterior descending artery. I thought it was the usual conservative med-speak when he warned me that I might need a heart transplant in the future.

congratulations for getting me there so quickly. There I met the first of many new friends: Dr. Mitul Kadakia, my new cardiologist. He calmly explained to me that I was having a heart attack. I don’t remember much until the next morning, when I woke up in a hospital room. Dr. Kadakia told me that I had a massive heart attack – something had blocked the “Widowmaker,” my left anterior descending artery. I thought it was the usual conservative med-speak when he warned me that I might need a heart transplant in the future.

The Complication. Even after discharge, testing continued. Dr. Kadakia had noticed that my aorta was distorted and could rupture — soon. The heart attack that nearly killed me saved my life, by revealing that the aorta was about to rupture. I then met with the head of cardiology at Stanford Medical Center, Dr. Joseph Woo, who assured me that this was something genetic (my grandfather died of an aortic aneurysm), and that the aorta was likely to rupture in the next year. He scheduled aorta replacement surgery for just before Thanksgiving 2014; he would do a bypass of the heart damage as well. In the meantime, I was doing cardiac rehabilitation to strengthen my system. I was soon able to walk two miles to work again without a problem.

The surgery went well, but recovery did not. Blood clots slowed my recovery, and I had a collapsed lung from the withdrawing of the tubes draining my chest. I had sleep apnea because of the pain pills, and there is nothing more frightening that waking up gasping for air. The bypass did not occur; the heart was too far gone for that. (“That’s bad!” I said when Dr. Woo told me. “Yes” was his loquacious reply.) While my aorta was repaired, my condition deteriorated, and I was unable to walk more than 25 yards without gasping for breath. I had chronic heart failure – my heart was unable to pump out enough blood. Without the blood, my kidneys were failing, filling me with fluid.

Another Try. Next, I agreed to try a CRT device. Not an old cathode ray tube TV that kids only sees in old movies, but a Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Device. It can act like a pacemaker or defibrillator, but its main purpose is to increase the heart’s efficiency by synchronizing everything. Unfortunately, damage had already set in; I was so sick that I needed a week of treatment to be healthy enough for the surgery. However, once it was in, I surprised myself by being able to go up and down a staircase like I had before the heart attack. I walked out of Summit on March 19th, seemingly back to normal. Within five days, though, I was back to feeling lousy, and I had an appointment with a Stanford heart failure doctor, Dr. Ranjan Ray. Dr. Ray turned my head to the left, looked at the right side of my neck very carefully, and told me that I was going to have a heart transplant. Dr. Ray explained that I had a vein on my neck that shows the extent of the chronic heart failure.

Freak Out. My mind flooded with headlines from the 70s, when heart transplants were new: Patient Watches TV 35 Days After Transplant; Transplant Patient Ailing; Patient Dies 56 Days After Transplant. I saw it as a extended death sentence; I wasn’t interested in surviving and suffering a few extra weeks. Dr. Ray, though, talked me through it, explaining how patients were living full lives after transplant, about how almost 90% last three years or more, and about how more and more patients who received their new hearts 20 or 30 years ago are still enjoying life today. I checked back in to Stanford the evening of March 24th.

Qualifying for a Transplant.

My Life as a Pincushion. To qualify for a transplant, I became a pincushion, giving 14 vials of blood, and several more every morning and evening for the next week. They checked my blood for various diseases, and to find the many markers that need to be matched for a good transplant. I had a colonoscopy and an endoscopy at the same time to make sure I didn’t have some disease that would kill me soon after the transplant, and thus waste a valuable organ. X-rays, an MRI, and a CT scan. A dentist pried open my mouth to verify my teeth were good. Passing the bar was minor compared to the stakes now. I passed the biggest tests of my life: I qualified for the transplant “list.”

It is not a list where you start at #21 and move up as those above you get a heart. Rather, it a prioritization: those (like me) with the most immediate need are in the first group, those who can wait for a while the second, and those with the least immediate need the third. When a donor heart becomes available, the donor network tests for thousands of markers to find the best match in the first group; if no one is close enough, it moves to the second group, then the third.

I learned that my A+ blood type made me a good candidate for a quick transplant. Soon enough, on April 10th, a nurse practitioner came to give me the good news that a donor heart was available for me. Then I waited. Waiting for my birthday or Christmas was never this agonizing — or consequential.

A New Heart. Finally, surgery began at about midnight on April 13th. I woke up a few days later. The nurse in super-intensive care asked me what day it was; I thought about it awhile, and declared “June 21st!” Nope. Tamayo needed my signature on an insurance document. I was quite impressed with my effort until I saw it a few weeks later – it was more a seismograph reading. Because the nurse wouldn’t give me enough ice chips (doctor’s orders), I had illusions that she was working with an organization trying to take over the world. Eventually, I reacquainted myself with reality, and transferred over to “regular” intensive care.

Back Up the Ladder. My recovery was easier this time. I had more energy. While I had hardly eaten between the two surgeries, I hadn’t lost any weight, as fluid replaced what had been in my body. I had chest tubes draining the fluid. I also had angels looking over my shoulder.

Physical therapy starts early

Angels on My Side. I’m not talking supernatural, or Victoria’s. I’m talking nurses, nurse assistants, and nurse practitioners, both male and female. They were uniformly professional and positive, even while dealing with the fluids that cannot be named. Don, a former Air Force nurse based in Iraq, was a huge help in assuring me that I would return to normal after the transplant. Rebecca was instantly like an old friend. Leilani gave me a waterless shampoo, so I stopped looking like a crazed Southern preacher. Cara took me to a jazz concert just outside my ward – where my feet started tapping like they used to. The tears of gratitude flooded my face. Getting my life back was a huge team effort, involving hundreds of people, and I’m tremendously appreciative.

The Donor. But there is one person I can never thank – the donor. Whose heart do I have? I don’t know his name, or how he died. That information will be kept confidential until at least April 2016. Even then, I can only send a letter to the organ registry, which will forward it to the donor’s family. They have the discretion to respond. I’m told that most do. I cannot imagine their pain. I hope that I will be able to thank them someday.

I left the ward on May 5th, but as an outpatient, I didn’t go far. We stayed nearby for a month, so I wasn’t far away when I returned several days a week for more blood work, echocardiograms (ultrasounds of the heart), x-rays, and heart biopsies – when doctors take small slices out of my heart through a tiny tube inserted through my neck. It doesn’t hurt much, but damn, when it slices the heart tissue, the heart jumps at the insult. The doctors need the tissue to see if there is any rejection – which hasn’t happened so far. Even better, after six months, the test for rejection is now just another blood test; what’s another vial?

2x/day. For life.

Pills Aplenty. Now, I only visit Stanford every few months. I am on immunosuppressants, and I will be for life, unless some future workaround is found (I’m betting on the doctors’ wizardry). Without a functioning immune system, I take antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals to fight infections, along with magnesium, calcium, aspirin, anti-cholesterol, and blood pressure medications. I take steroids to repair the damage which make my hands jittery. When I took higher doses of steroids, they thinned my hair and nails, and my skin would get cuts just from stretching it. The steroids have given me medically-induced diabetes, and I get medications for that. It may be only temporary, but there is probably enough damage to make it permanent.

I still have a long way to go to return to “normal.” But I can cycle, swim, and hike like I could before all the troubles. I love being a lawyer, a father, a husband, a friend, and a human being again.